The Engine-Generator of Workouts

From bib. source

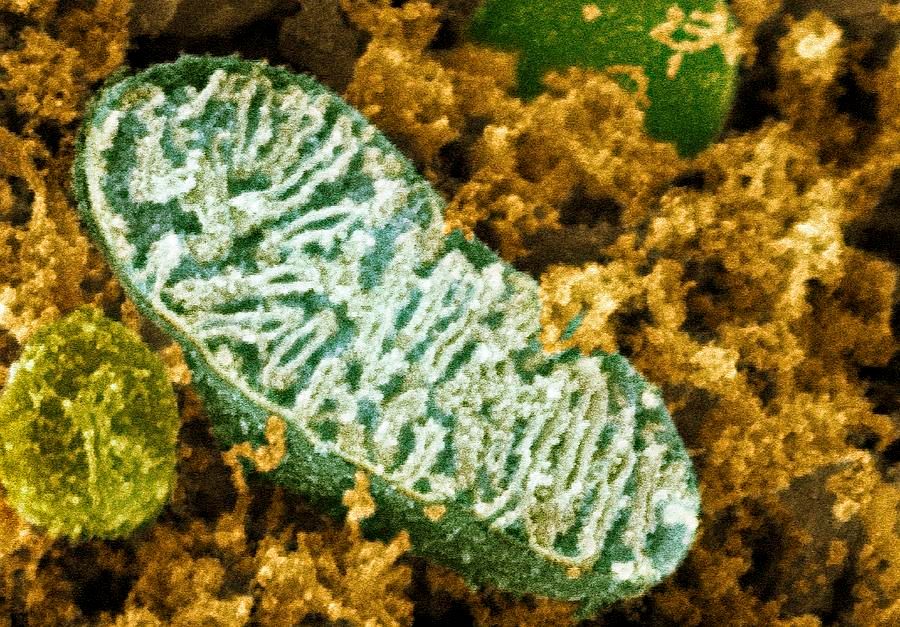

The ultimate power molecule in the body is ATP (adenosine triphosphate). […] How efficiently you generate and use this ATP determines how fast, powerful, and enduring you can be as an athlete. When you exercise in aerobic (oxygen rich) conditions, your mitochondria can generate 34 ATP per glucose. When you exercise in anaerobic (low oxygen) conditions, your cells use less efficient glycolysis, which generates only two ATP per glucose. Therefore when your cells have enough oxygen, they are 17 times more energy efficient.

As mentioned above, ATP–adenosine triphosphate–is the power supply, or “power molecule,” of the human body (LeMond 2015, 20). That is to say, it is how the body gets or has energy (Ibid). And yet, the supply of this power depends on the efficacy and presence of biofuel, a type of organic fuel so to speak, as well as reactant.

In our case, the fuel in question is either circulating glucose (or fructose), or stored glycogen (such as that found in fat or fatty tissue)–the relative quantities of either fuel mediated by the liver in the blood sugar regulatory system. The absolute quantity of both fuel forms is constrained by the gastrointestinal tract within the digestive system over the short-, medium- and long- term. The essential reactant for human bodies is oxygen, which can only be in short-term supply at any given moment (hence the need to be constantly breathing while the heart constantly pumps to distribute that reactant throughout the body).

Oxygen is thus essential to the production of ATP–or at least to the most efficient or the (sub)optimal production of ATP–by mitochondria provided there is also enough fuel to burn during a given exertion. As aforementioned, exercising in oxygen-rich (aerobic) conditions allow mitochondria to generate 17 times more ATP per glucose than that generated during glycolysis that occurs under oxygen-deprived (anaerobic) conditions (Ibid). As for sufficient fuel, since the muscles / skin and liver “can store energy as glycogen and fat, food is usually not the rate-limiting factor in performance (at least for short and medium duration exercise)” (Ibid). Instead, “improving oxygen delivery to the muscles can make a dramatic difference in physical performance” (Ibid). This is because “[w]ith proper physical training an athlete builds more muscle and more mitochondria and therefore has increased oxygen demand” (Ibid).

Carbohydrate-rich caloric intake dial modulates endurance, oxygen saturation dial modulates performance

That is, while people need to be eating good amounts of food to take advantage of and increase our power, the amount of high-carbohydrate (especially non- whole grain based) or easy-to-digest foods we need to eat prior to workout decreases as the amount of glycogen or fat that happen to be in people’s bodies prior to workout increases. This means that bio-fuel supply provides the ceiling for workouts, hence affect maximum endurance. Reactant supply, i.e. oxygenation or oxygen saturation, on the other hand, affects the ceiling of the efficiency or optimality of the workout (in terms of, for example, kinetic repetitions at a fixed intensity per minute). The latter may have benefits for what many athletes and sports scientists might call “explosive power.” This implies that breathing technique is very important during and right before a workout session, and that breathing exercises or breath training may improve conditioning towards beneficial breathing techniques. Further, since oxygen demand increases with improved fitness as aforementioned, breathing that aids increases in total oxygen supply per breath or decreases in total wasted oxygen per breath will increase performance along with strength or muscular power.

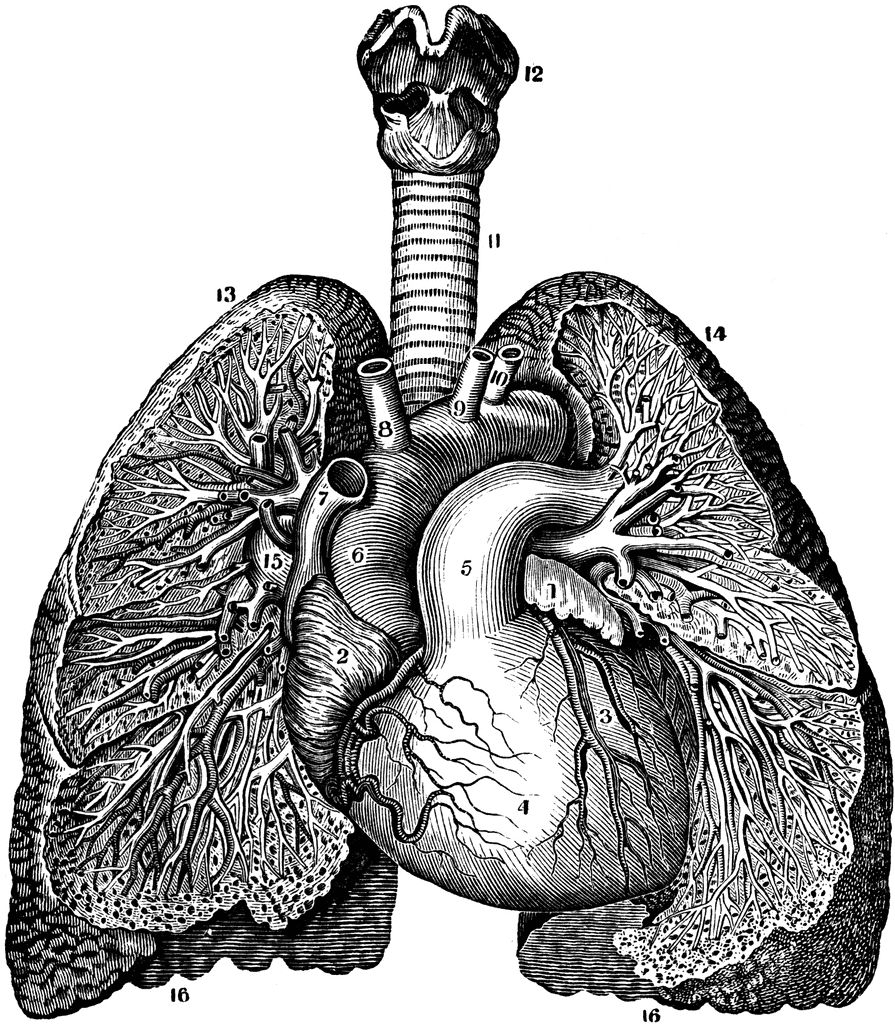

Oxygenating the body relies on what is called the oxygen delivery system, which is the interaction between the pulmonary circuit and the circulatory system (Ibid):

From bib. source

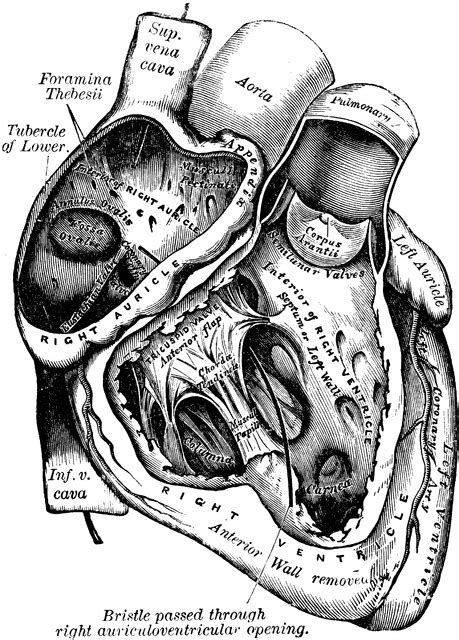

The oxygen delivery system […] consists of the heart (pumping), lungs (gas exchange), and the blood and blood vessels (transport). In the short-term this oxygen delivery system makes rapid and dramatic changes from rest to all-out effort. In the long-term the heart adapts to training and becomes stronger as a pump. Strengthening your heart and strengthening your skeletal muscles are the basis of fitness improvement.

Reactant Supply as a Function of Cardiac Efficiency

The behavior of the heart in response to immediate, contemporaneous activity is to shift is rate (LeMond 2015, 20-21):

From bib. source

Efficient pumping by the heart does not just depend on the total blood or blood cell supply itself (hence the importance of protein in the diet as well as the importance of long-term oxygenation), but on the proper coordination of the neural conduction system or neural conduction circuit leading to well-timed cardiac muscle contractions (LeMond 2015, 21):

From bib. source

Heart rate is determined by a complex interaction with our nervous system that involves chemoreceptors (oxygen and carbon dioxide), baroceptors (blood pressure), and the conduction system in the heart. The heart is connected to the brain, but subconsciously. […]. Like other nerves in the body, the conduction system in the heart is very reliant on mitochondrial energy.

Indeed, a heart rate (beats-per-minute) well-regulated by the neural conduction circuit is important to ensure timely and proper allocation of oxygen where it is needed during exercise; nevertheless, the more important measures in the long-term are ejection fraction (pump efficiency, or the fraction of the total blood in the body that is ejected by the heart on each contraction) and, as aforementioned, stroke volume (blood moved per pump) (Ibid). After all, in the long-term the heart adapts to the increased demand for oxygen from muscles’ whose long-term training had lead to increased mitochondria or higher mitochondrial density by increasing the volume of the heart’s chambers (impacting ejection fraction) or hypertrophying its chambers (impacting stroke volume) (LeMond 2015, 21):

From bib. source

With training that is challenging enough to get the heart beating faster and stronger, the heart responds in several ways. The muscular walls of the left ventricle of the heart become thicker (hypertrophy) yet remain pliable, the left ventricular chamber becomes larger (between contractions, allowing greater filling), and the heart can empty more completely as it squeezes and contracts. Thus with each beat, the heart is moving more blood in a more efficient manner.

Hypertrophied cardiac chamber walls, though, can have the downside of actually decreasing stroke volume if the hypertrophy was due to to intrinsic properties or features of the blood vessels, such as “aortic valve stenosis” (narrowing of the largest artery), which can show up in high blood pressure among other symptoms (Ibid).

Cardiac diet and healthy hypertrophy

The above is why a diet that avoids changes in properties or features of blood vessels, and other aspects of the cardiovascular system, is just as important to cardiac health as intense aerobic exercise: it ensures hypertrophy occurs along with stroke volume improvements, rather than independent of them.

Given the heart is an organ that in the short-run depends on mitochondria that themselves in the short-run depend on oxygen transport via cardiac muscle contraction, any disruption in either can lead to the other over- or under- shooting during exercise. Hence, one should keep oneself, during strength or resistance training, within a given range of heart rate called a heart rate zone in order not to overexert cardiac muscles and the lungs; otherwise, during endurance training, one should carefully try to find techniques that help adjust heart rate in accordance with the stages of the given exercise in order to avoid depleting all possible bio-fuel during or by the end of exercise (Ibid).

Aerobic endurance training and pre-workout diet

In addition, given that “[h]eart mitochondria rely mainly on” glycogen stores, i.e. fat, ”as fuel,” aerobic exercises that do not fall under strength or resistance training need the least amount of pre-workout carbohydrate calories relative to extant fat in the person’s body, as well as the least absolute amount of calories overall whether pre- or post- workout.

Reactant Supply as a Function of Pulmonary Efficiency

As mentioned at the beginning, managing the supply of reactants (in this case, oxygen) is key to athletic, sports or exercise performance, and reactants are the key resource allocated and distributed by the heart. However, it is the lungs that are primarily responsible for the available short-term supply of oxygen for the heart any given moment, which makes them a central, essential component of the pulmonary circuit.

Given the aforementioned, so long as the body has efficient heart pumps and an adequate supply of bio-fuel, the lungs allow us to maximize or optimize the use of these across a workout session, as (Ibid):

From bib. source

The lungs are another key part of oxygen delivery. As we exercise, we breathe faster and more deeply.

Thus, it is important to recognize that (Ibid):

From bib. source

To some degree we can increase our breathing efficiency by using and strengthening our diaphragm and rib cage muscle. But unlike our muscles or heart we cannot grow new lung tissue.

That is, the diaphragmatic muscles and rib cage muscles key to the inflation and deflation of the lungs, allowing for adjustment of air supply, can grow new tissue just as any other muscles, and that growth can aid lung capacity among other things (Ibid).

However, the lungs themselves cannot grow new tissue (Ibid). The alveoli especially–that are “delicate tiny air sacs” across the inner surface of the lungs responsible for “oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange”–cannot be grown anew and so must be protected by avoiding “diseases, air pollution, and infections” of the lungs (LeMond 2015, 22). “Cigarette smoking” especially is “very damaging to the lungs” as it can potentially “cause irreversible death of alveoli,” and should be heavily avoided (Ibid).

Breathing techniques should target the diaphragm

To increase breathing efficiency in the long-run, it is important to implement breathing techniques that allow the hypertrophy of the diaphragmatic muscles, so more air can be pulled in and pushed out more quickly, allowing for increased performance during workouts (i.e., more kinesis per caloric expenditure).

Do exercises that target chest or abdominal muscles

Exercises that target chest muscles in particular can have a long-run effect on rib cage muscles, allowing the lungs more room for expansion by contracting ribs back. Nonetheless, both chest and abdominal muscle exercises are likely to benefit breathing efficiency in the long-run.

Maintain direct relationship between diaphragmatic and rib cage muscle strength

When exercising for breathing or pulmonary efficiency, one should ensure that rib cage muscle strength increases with any proportionate increase in diaphragmatic muscle strength.

adenosine_triphosphate athleticism sports_science biology physiology cytology pulmonocardiac_pathway pulmonary_circuit circulatory_system respiratory_system aerobic_exercise aerobic_exercises anaerobic_exercise anaerobic_exercises BEAST_fitness_system BRATS_fitness_system pulmonology biological_economics cardiology metabolism adenosine adenosine_triphosphate adipose_tissue blood_sugar_regulatory_system digestive_system gastrointestinal_tract circulatory_system pulmonocardiac_pathway pulmonary_circuit breathing_exercises breathing_exercise exercise digestion tophology nutrition absolute_quantity relative_quantity negative_correlation inverse_relationship oxygen_saturation fitness myology kinesiology muscular_system muscular_power muscular_performance muscular_endurance athletic_performance athletic_endurance athletic_strength oxygen_delivery_system skeletal_muscle skeletal_muscles musculoskeletal_system resistance_training endurance_training heart_rate stroke_volume blood_cells contraction muscle_contraction neural_conduction_system nervous_system heart_rate_zone lung left_ventricle hypertropy chamber left_ventricular_chamber heart_chamber cardiac_chamber blood_flow blood_pressure inflation deflation chemoreception baroception rib_cage air_sac cigarette cigar cardiovascular_system organ_system organ_systems biological_economics

bibliography

- “The Human Machine.” In The Science of Fitness: Power, Performance, and Endurance, 9–38. Waltham, MA: Academic Press, 2015.