Conceptualizing Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome

Reasons for the PDA syndrome construct

From bib. source

The term Pathological Demand Avoidance syndrome (PDA) was first used during the 1980s by Professor Elizabeth Newson. The initial descriptions were introduced in a series of lectures, presentations and papers that described a gradually developing understanding of a group of children who had been referred for diagnostic assessment at the clinic based at the Child Development Research Unit at Nottingham University. This clinic […] had a specialism in children who had communication and developmental difficulties. Most of the children referred […] reminded the referring professionals of children with autism or Asperger’s syndrome. At the same time, […], they were often seen as not being typical of either of these diagnostic profiles.

Essentially, the referral of a particular population of children in the 1980s to a clinic in the Child Development Research Unit at Nottingham University for possible autism or Aspeger’s syndrome–whom were at the same time not typical in their presentation of these conditions or syndromes–lead to the gradual development of a set of clinical descriptions that attempted to understand and classify such children (Christie 2012, 122). The term which emerged to encapsulate these descriptions and thereby classify this population was Pathological Demand Avoidance syndrome (Ibid). There is one major reason for the construction of this syndrome–though this major reason has more than one support.

Inadequacy of autism and Asperger’s constructs for PDA children

From bib. source

Newson and her colleagues began to feel increasingly dissatisfied with the description of ‘atypical autism´, which was frequently used in the UK at that time. In the USA pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) was the term used to mean the same. They felt that it was unhelpful to parents to be told that their child was not typical of a particular condition. Neither was it useful in remove confusion that was often felt by those who were struggling to gain greater insight into their child’s behavior.

For one, in other words, both autism and Asperger’s syndrome seemed inadequate, or other times misleading, when it came to understanding and developing guidelines for this particular population of children who seemed to have some kind of pervasive developmental disorder, or PDD (Christie 2012, 11-12). Simply labeling these children as having an unspecified pervasive developmental disorder, or PDDNOS–while convenient–does not improve such a situation, as the lack of specification is exactly what leads to problems predicting and explaining the behavioral issues and precise developmental pitfalls of these children (Ibid). The major distinguishing traits of the population of children at hand, from a typical autistic or Asperger’s syndrome presentation, were (a) their level of social understanding, and (b) their capacity for imaginative play (Christie 2012, 12).

From bib. source

[…], Newson began to notice that while these children were indeed atypical of the clinical picture of autism or Asperger’s syndrome they were typical of each other[sic] in some very important ways. The central feature and characteristic of all the children was ‘an obsessional avoidance of the ordinary demands of everyday life´ (Newson 1990, p.1; see also Newson, Le Marechal and David 2003). This was combined with sufficient social understanding and sociability to enable the child to be ‘socially manipulative´ in their avoidance. It was this level of social understanding, along with a capacity for imaginative play, which most strongly countered a diagnosis of autism.

However, the need to classify or label these individual cases in a way that has utility for prognosis, did not by itself indicate that the population of children appearing at the Child Development Research Unit’s clinic had need for a shared classification or label. That said, this population of PDD-NOS or “atypical autism¨ cases shared in common being referred to the clinic for autism or Asperger’s syndrome. This indicates either overlapping features or at the very least some family resemblance to the other pervasive developmental disorders, that would encourage a hypothesis that this population–or at least a sub-population of them–must share, if not some condition or syndrome, a diverse array of them under similar domains. And in fact, by the 1990s clinicians had begun to observe that many of the children in this population were very typical of each other even if they were atypical of autism or Asperger’s syndrome (Christie 2012, 12). The behavioral patterns among these children were seen to share the common result of avoidance of everyday demands of life (Ibid).

From bib. source

Through a series of publications, based on increasingly large groups of children (up to 150 cases) and supported by follow-up studies (Newson and David 1999), the clinical description of PDA was refined and the differences between this profile and those found in children with a diagnosis of autism or Asperger’s syndrome made clearer (Newson 1996; Newson and Le Marechal 1998). The studies also demonstrated the robustness of the clinical descriptions from childhood into adulthood. These publications culminated in a proposal (Newson et al. 2003) to recognise PDA as ‘a separate entity within the pervasive developmental disorders’ (p.595). Newson proposed that the clinical description of PDA be conceptualised as a separate identity as it gives ‘specific status to a large proportion of those children and adults who earlier might have been diagnosed as having pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified’ (p.595), a much less helpful diagnosis in terms of guidelines for intervention.

Increases in clinical and academic publications and experimental studies through the late 1990s and early 2000s had allowed refining of the many associated traits and behaviors common among that population of children then characterized as demand-avoidant (Ibid). This also allowed more precision in discriminating between autism and Asperger’s syndrome diagnoses and demand-avoidance symptoms, so (Ibid). Eventually, the early 2000s saw Professor Elizabeth Newson able to actually propose demand avoidance as part of a cluster of symptoms forming a distinct, semi-independent syndrome, i.e. as Pathological Demand Avoidance syndrome (though she had already coined the term in the 1980s) (Ibid).

From bib. source

The controversy that exists, […], has been about whether PDA does exist as a separate syndrome within the pervasive developmental disorders or whether the behaviours described are part of the autism spectrum.

Despite that, the degree of independence the syndrome has from other pervasive developmental disorders, and whether the syndrome is part of the autism spectrum, continued to be of controversy from the 2000s onwards (Christie 2012, 13-14).

From bib. source

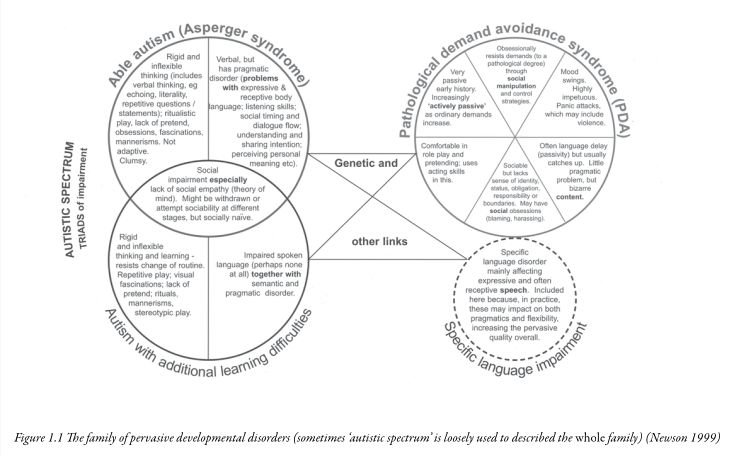

Diagnostic systems and categories, though, as well as showing variation in the way they are used by different professional groups or individuals, are also evolving and developing concepts. […] Newson recognized this when devising a diagram (Newson 1999) to demonstrate how she thought of PDA as a specific disorder that, along with other disorders including autism and Asperger’s syndrome, makes up the ‘family´ of disorders known as pervasive developmental disorders (see Figure 1.1).

Elizabeth Newson’s approach at the time was to treat autism, Asperger’s syndrome and the newly-scientifically-minted Pervasive Demand Avoidance syndrome as distinct clusters of symptoms with some core or essential underlying traits/drivers/causes that nonetheless formed a family of pervasive developmental disorders. By family is meant that they all had occasionally overlapping symptoms–especially for the more superficial symptoms–and that a child that has pervasive developmental issues could land anywhere among these clusters (Christie 2012, 14). A diagram is available below (Ibid):

Figure 1.1 from bib. source

Hypothesis: separate PDDs arise from the state or vectoral variability in essential, core distinct dimensions or state spaces shared among all the PDDs

From bib. source

The diagram shows ‘clusters of symptoms´(syndromes) that represent specific disorders within the pervasive developmental disorders. Newson saw PDA as a separate syndrome related to autism and Asperger’s syndrome and pointed out that there may be some children who fall between these ‘typical clusters´ (i.e., they share characters of both syndromes). The caption for this diagram of the family of pervasive developmental disorders includes the note: sometimes ‘autistic spectrum´ is loosely used to describe the[sic] whole family[sic]. In adding this Newson foresaw what has subsequently taken place.

Notably, this view from Elizabeth Newson allowed her to predict the expansion of the meaning of the “autism spectrum¨ to come to describe what she characterizes as the entire family, rendering it practically synonymous in what it captures to the term “pervasive developmental disorders¨ (Ibid).

Diagnostic criteria for PDA syndrome construct

The 2003 specification of diagnostic criteria for PDA syndrome either drafted or mentioned by Newson is as follows (Christie 2012, 13):

- Passive early history in the first year.

- Asocial passivity to resistance path: High “proportions of children with PDA were described by their parents as passive or placid in the first year of their life¨ (Christie 2012, 18). Examples of such passivity or placidity are a lack of reaching for toys, or actively dropping toys when toys were offered. In some cases, the child “begins to become more actively resistant as more is expected of him¨ albeit others “are resistant from the start¨ (Ibid). This is often highlighted in group settings (Ibid). That being said, this feature of PDA, while typical, “is by no means universal and should not be seen as essential to the diagnosis¨ (Ibid).

- Continues to resist and avoid ordinary demands of life. . .strategies of avoidance are essentially socially manipulative.

- Anxiety management over control loss as avoidance motive: The motive for this can be understood to be “an anxiety-driven need to be in control and avoid other people’s demands and expectations[sic]¨ (Christie 2012, 19). More specifically, there is “an extreme anxiety about conforming to social demands¨ and “of not being in control of the situation,¨ i.e. of the situation that produces or makes the social demand possible (Ibid). Consequently, sometimes even “any[sic] suggestion made by another person person can be perceived as a demand¨ (Ibid). This “inability to accept situations¨ unless they had been in control of “the way in which¨ it “should take place¨ can prevent enjoyment of “an experience altogether,¨ even if the situation is conducive to activities or experiences the child would otherwise likely have enjoyed (Ibid).

- Socially astute avoidance strategies: A key difference in social avoidance strategy compared to autism is that, instead of asocial tactics, “the child has sufficient social understanding and empathy to be socially manipulative in their endeavours,¨ adapting “strategies to the person making the demand¨ (Christie 2012, 20). Strategies that may be used include: distracting from or procrastinating on the demand, rationalizing lack of execution, front-loading the demand to delay execution, negotiating to exert control over the situation, or escapism (Ibid). As a last resort, “straightforward refusal or outbursts of explosive behaviour including violence¨ may be used (Christie 2012, 22). Though it is important to note “[n]ot all children with PDA have explosive outburts¨ though it “seems to affect a significant number¨–about (Christie 2012, 23). Tolerance levels mediates the frequency as well as intensity (or escalation) of demand avoidance (Christie 2012, 22-23).

- Surface sociability, but apparent lack of sense of social identity, pride or shame.

- Deployment of social understanding for demand avoidance behaviors–unclear emotional empathy, limited social empathy: There’s a tendency towards being “very ‘people-orientated´¨ due to an alertness to possible requests (Christie 2012, 23). They adopt social niceties to facilitate declining requests, or attempt to charm so they are allowed opportunity or leeway to skirt expectations (Ibid). This highlights a difference in social understanding and empathy compared to those who are autistic (Ibid). Nonetheless there remains some similarity insofar as “the sociability tends to be skin deep¨ as “[t]heir social approaches and responses can be unsubtle and without depth,¨ perhaps from not knowing what level of response for shirking a particular demand is required (Ibid). It is not clear to what extent the social empathy of such children involves emotionally empathy in addition to cognitive empathy (Christie 2012, 24). They at least know that “a particular behaviour or attribute may have a specific outcome with an individual¨ (Ibid).

- Poor social judgment demonstrated via enacting ambiguous responses to social reward: The degree of poor social judgment the children do have is manifest “in an ambiguity in their mood and responses.¨ There is an ambiguity in how the children responds to a phenomena like “praise by insisting that it’s not meant or by destroying the work that you have just commented on¨ (Ibid). This demonstrates “both their own confusion and the fact that their behaviour can be confusing to others¨ (Ibid). It may be helpful to speculate how this ambiguity connects to other symptoms. (One can conjecture it is downstream from other symptoms, such as the second diagnostic criterion.)

- Inconsistent or absent identity leading to issues with maintaining or respecting boundaries, issues with recognizing authority and issues with being able to perceive the situational relevance of particular sets of social rules: It is notable too that this is often accompanied by “an enormous difficulty for the child in developing a sense of what she described as ‘personal identity´¨ (Christie 2012, 25). For example, it is common that PDA children fail “to identify with other children as a group and more naturally gravitates towards adults¨ (Ibid). More concrete manifestations of this may be acting like a parental figure or guardian to same-age peers, relating well to adults, preferring being with adults, or responding more favorably to adult styles of speech (Christie 2012, 26). Those with PDA may consequently “fail to understand many of the unwritten social boundaries or divides that exist, say between adults and children,¨ and this can manifest as problems with authority (Ibid).

- Weak social identity leads to weak response to social status related stimuli: Children with PDA seem to “lack a sense of pride or embarrassment and can behave in very uninhibited ways that are out of keeping with their age and pay little attention to the attempts of adults to appeal to ‘their better nature´¨ (Christie 2015, 26). This leads them to “difficulty in accepting social obligation and taking responsibility for their own actions and behavior¨ (Ibid).

- Lability of mood, impulsive, led by need to control.

- Lability of mood as attempt to regain control irrespective of demand content and externalize anxiety over loss of control: It has been observed that mood switches occur rather suddenly among those children with PDA, and that such children commonly have “[d]ifficulty with regulating emotions,¨ the latter of which PDA would then seem to share with autism spectrum disorders (Christie 2012, 27-28). That said, “[e]xcessive lability (or changing) of mood¨ is “especially prevalent in PDA,¨ as it was found in “68% of the PDA group¨ and made it easy to discriminate between PDA children and children with classical autism or with Asperger’s in Newson’s studies (Christie 2012, 28). This, in addition to impulsivity, persisted “beyond childhood in the majority of those with PDA¨ (Ibid). The radical switching of moods in PDA are linked to the social ambiguity of the child’s behavior, as described under symptom #3 (Ibid). Both this symptom and that one may be motivated by the same need to be in control (Ibid).

- Comfortable in role play and pretending

- Social dissociation through role play or pretend as strategy to reassert control over a social situation and re-establish safety: Like with autism, there may be present a “long-standing interest in role play and in acting out characters¨ (Christie 2012, 21). In other words, “[c]hildren with PDA often mimic and take on the roles of others, extending and taking on their style¨ (Christie 2012, 29). The difference with autism is that this does not involve “simply repeating and re-enacting what they may have heard or seen in a repetitive or echoed way¨ as if forming part of a patch quilt repertoire of tools for socializing (Ibid). To be clear, this interest in role play and playing pretend seems to subsist independently of its utility for demand avoidance strategies in children with PDA, yet when opportune it will be incorporated into those strategies for avoiding demands or exerting control over events and people (Ibid). Sometimes, a given bout of role playing can scale up to being quite extensive in operation, becoming an object of obsessive fascination (Christie 2012, 30). It is alleged PDA children playing pretend may even seem “to confuse reality and pretence at times¨ (Christie 2012, 29).

- Language delay, seems the result of passivity: good degree of catch-up.

- Link between anxiety over loss of control due to social demands, and disruptive delays in processing language: This language delay observed to afflict “the huge majority of children with PDA¨ is part of a general passivity, as described in symptom #2 (Christie 2012, 30-31). However, after delay, there is an accelerated development of language abilities, allowing these children to catch up (Ibid). Nonetheless, there are a few observable patterns of problems PDA children have with language, despite their verbal fluency: often taking things literally, often not understanding sarcasm or teasing, and often processing speech–or language more generally–slowly enough to disrupt communication flow (Christie 2012, 31). These difficulties arise particularly when the PDA child is not in control (Ibid).

- Obsessive behavior.

- Fixations on specific individuals and deep engagement with role play that can lead to social improprieties: “[…] [T]he demand-avoidant behaviour itself usually has an ‘obsessive feel´¨ and obsession is also felt in PDA children’s “strong fascination with pretend characters and scenarios¨ (as discussed under symptom #5) (Christie 2012, 32). It is observed that “the subjects of fixations for children with PDA tend to be social in nature and often revolve around specific individuals,¨ which when combined with the children’s confused boundaries and insensitivity to social status (discussed symptom #3) may lead the children to encounter situations of “blame, victimisation, and harassment,¨ causing “real problems for peer relationships in school¨ (Ibid).

- Neurological involvement.

- Clumsiness or physical awkwardness during demands and delays in developmental milestones: This symptom has been under-researched (Christie 2012, 32). However, some studies indicate late or absent crawling “in more than half of the children concerned¨ (Ibid). In a significant minority other milestones, e.g. age of sitting, are delayed (Ibid). “Clumsiness and physical awkwardness are quite common and many were described as ‘flitting´ in attention¨ (Ibid). The catch, however, is that “more than a third […] only showed this behavior when demands were being made¨ (Ibid).

Hypothesis on demand avoidance: privatization of social fantasy (of fantasies about society) as universal underlying strategy of avoidance

Perhaps the observed lack of shame, pride or sense of obligation/responsibility in children with PDA–as discussed in symptom #3–is because they cannot properly locate the socioculturally legitimate perspective to view a situation from. And they cannot do this because locating what perspective is socioculturally legitimate requires a sense of identity. The result is the inability to perceive the relative relevance or value of social rule-sets to the effects of their behavior on, or to the prescribed constraints on their behavior by, social status.

In such a case, though, more technically it is not that children with PDA lack pride or embarrassment/shame or even responsibility or a sense of obligation, but that external social feedback are not able to weigh on those emotions, affects or experiences as much. This means social situations where we would culturally most often expect to see pride, shame, sense of duty or responsibility operative do not seem to consistently produce these to the same degree as it would in someone from an experimental control group. Thus, when and whether the PDA child will yield or concede to social rules becomes apparently unpredictable.

It is important to differentiate this from an antisocial regard towards social rules, as the rule-breaking from antisocial traits is done in spite of understanding the situational value and relevance of a behavioral rule. Someone with antisocial traits breaks the rules because doing so is viewed as the quickest or most effective way to achieve an egotistic or narcissistic goal–sometimes they may even do it for its own sake as that may validate a narcissistic fantasy. By contrast, an adult, if not a child, with PDA can see long-term consequences and make decisions based on that. A child with PDA also neither necessarily sees social rules as general goal impediments nor sees rule-breaking as inherently validating of self-worth. The best way to put it is that PDA leads to the child subjectivizing the social rules–they either think they are, or they wish to see themselves as, the draftsman of the social rules irrespective of external input.

This subjectivization of social rules is more accurately described as an asocial trait, and whether it ends up producing prosocial or antisocial behavior, or rule-breaking, and in what balance is particular to the person with PDA. This also makes sense of the peculiar importance role play and imaginative play has to those with PDA, as in symptom #5: role play and pretend empowers them to arbitrarily shift, not reality as such, but social reality. Essentially, the normative experience of “social facts¨ (arguably, a public fantasy socially reinforced by the material forces it itself rationalizes) is replaced by an idiosyncratic or privatized social fantasy. This is also consistent with the occasional escapist strategies for avoiding demands discussed for symptom #2, but the privatization of social fantasy likely underlies all demand avoidance strategies.

Under this hypothesis, any alleged confusion a PDA child may show between reality and pretence is a confusion that occurs exclusively or predominantly in the social domain. Observations regarding symptom #7 seems to provide some evidence for this.

Hypothesis on impulsive emotional lability in PDA: dialogical decision-making contexts trigger impulsive emotional lability as it initiates a content-indifferent struggle for control

That, as stated in symptom #4, the impulsive emotional lability and social ambiguity (described in symptom #3) are both motivated by a need to be in control would seem to predict the impulsive lability of mood showing up primarily in dialogical decision-making contexts. A key aspect of this is that the struggle of control is not actually concerned with the content of the decision-making (e.g., the end-result or the semantics of the proposals), but with unilateral determination of its form or procedure.

Of course, it should be clear that (Christie 2012, 17):

From bib. source

As further research takes place, and our understanding of PDA is refined, it is likely to be the case that the original list of criteria will be reduced. This will distinguish those criteria that are essential for a diagnosis, from those that are commonly associated but not necessarily found in all children. This is a similar process to that which took place in earlier formulations of autism, when longer lists of symptoms were reduced to […] three features […] .

pathological_demand_avoidance_syndrome diagnostic_criteria language_delay pervasive_developmental_disorder pervasive_developmental_disorders social_identity role_play pathology psychopathology abnormal_psychology psychiatry psychology Elizabeth_Newson Child_Development_Research_Unit Nottingham_University Aspergers_syndrome atypical_autism pervasive_developmental_disorder_not_otherwise_specified child_psychology symptom_profile social_manipulation imagination play developmental_disorder developmental_disorders guideline autism_spectrum autism_spectrum_disorder autism_spectrum_disorders family_resemblance asociality judgment social_judgment social_empathy emotional_empathy cognitive_empathy ethology toy social_status social_identity personal_identity control_group experimental_control_group antisocial_trait asocial_trait antisocial_behavior prosocial_behavior verbal_fluency language_processing narcissism dimension dimensions state_space state_spaces vector vectors variation diversity social_science

bibliography

- “What Is PDA?” In Understanding Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome in Children: A Guide for Parents, Teachers and Other Professionals, 11–40. JKP Essentials. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2012.